|

Two days ago I found myself weaving through a dense crowd, my right hand gripped tightly on my son Calvert and my left hand clasped on my nephew Harold. We were making our way to Boston Harbor to watch the theatrical reenactment of the Boston Tea Party when suddenly the throng closed in. In that moment it occurred to me that I hadn’t felt this kind of frenetic group energy since seeing the Rolling Stones at Giants Stadium as a teenager! But here for the 250th anniversary of a historical event, it was a crowd of more 30,000 gathered along the Harborwalk not to be educated or entertained but to bear witness to a ritual of remembrance.

As we were inching forward, I heard one of the orange-vested staff (volunteers?) shout to a colleague, “there’s already 5,000 more people here than we originally expected, and this doesn’t start for another hour!” Indeed, there were many more on the way, I knew this as I had been receiving messages from Holly Walters who was on Pearl Street following the “Rolling Rally” march led by Fife and Drum music with another few thousand spectators trailing behind. There were groups of reenactors in 18th century garb, more Ben Franklins and George Washingtons than I could count and plenty of tourists who had thrown on a tricorn hat to join in the spirit of the evening. As they passed the tap houses near the wharfs, groups of men and women with beer mugs in hand were drawn outside to line the streets and cheer them along. Anthropologists will tell you that engaging in acts of “Ritual Drama” like this is a universal, cross-cultural behavior - the exercise of commemoration puts us in touch with our human nature. As momentum builds, people are drawn into the action and derive a sense of belonging and meaning from participation. In our secular society, these opportunities are often centered on mythologizing the Founding history of our Nation. This “ritualizing” of history was on grand display with the heavily narrated, theatrical 30-minute summarization of a Boston Tea Party (simultaneously live streamed to the Nation) showcasing a polished version rather than an exact history. But the dramatization accomplished what it intended to do on an emotional level and those wanting to know more were able to crack open replica tea chests with an ax in Boston Common or attend exhibits and events that were presented by a variety of historical institutions in the weeks leading up to the commemorative date. From an educational standpoint, the digital footprint of social media postings, video conference presentations and commemorative research will likely shape our public understanding of this historical event for 50 years to come. Some of the onlookers who congested the downtown for the 250th anniversary night were Bostonians but the vast majority were people like me, tourists who had booked a few nights in a downtown hotel, dined throughout the city and loaded up on souvenirs to bring back home to family and friends. Unlike a concert or a sporting event at a stadium, the economic impact of Heritage Tourism is not contained to the tight timeframe of the event itself. It is well documented that heritage events have more than a 7-to-1 return on investment because Heritage Tourists stay longer, spend more money, and develop long lasting connections to a place that cause them to return for repeat visits. But on this particular December 16th, the takeaway for me was that perhaps because of all the distractions of modern life, access to endless scrolling on personal devices, worry in the profession about growing historical illiteracy, and the diminution of government investment coordination of important commemorations, there was genuine surprise about just how popular this “happening” ended up being. It was clear that the City of Boston left much of the work to volunteers and loosely organized (notoriously underfunded) historical stakeholders. There was not enough signage through the city in the days leading up to the event, hotel workers seemed to be unaware of the significance, I never saw any notable Police presence and staff (volunteers?) bearing the America 250 logo at the reenactment itself were quickly overwhelmed and unable to keep walkways safely clear during the event. It was a lesson in the popularity of historical commemoration, the apathy of government support and a reminder that if local planners design, fund, promote and staff these events properly, they have the potential to have a powerful impact on our local economies and tourism branding. Stakeholders in the historical community put together great programming, but not enough support was visible from the government partners who stood to benefit most from it. Imagine if even a fraction of the resources usually allocated to ticker-tape parades or music festivals had been directed here. There were no food trucks, souvenir vendors, or cab stands, none of the usual amenities expected at a public gathering of this size. Lucky for us in Orange County, we can look to Boston Tea Party 250th as an example and warning. Just as the theater of war moved south to the Hudson Valley following the early events of the American Revolution in Boston, so too will the focus shift in the years to come. With New York State and especially the region surrounding West Point at the heart of important anniversaries from 2024 to 2033, I encourage local elected officials, municipal historians, teachers and historical society volunteers to capitalize on the commemorative opportunities on the horizon.

0 Comments

A Resolution of the States Gathered in Partnership on the 250th Anniversary of Virginia’s Committee of Correspondence Williamsburg, Virginia March 12, 2023 Two hundred and fifty years ago, a disunited people began a correspondence and rallied to a common cause, which three years later culminated in the establishment of the United States of America. Our American experiment is unique in human history—a government of laws and not of individuals; a government by the people and for the people, founded on the self-evident truth that all are created equal and are endowed with the universal rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In the ensuing centuries, our nation, through the determination of its people, and with its boundless capacity for reinvention and renewal, has progressed in its journey, bending towards justice, and striving to fulfill by struggle and sacrifice the promise of the Revolution for all Americans. Inspired by the approaching 250th anniversary of our nation’s founding, we gathered here, resolve to commemorate our shared American story, recognizing its fullness and complexity, its achievements and shortcomings, and by honoring the many voices that together forge one nation. We pledge ourselves to a new common cause—for all Americans to unite in reflection, celebration, and aspiration as we continue our national journey together. We call on all Americans to embrace this historic moment—extraordinary in our lifetimes—as it is incumbent upon us to collectively renew our commitment to the unfinished pursuit of a more perfect Union, and to forever advance the ideas that inspired the Revolution…liberty and justice for all. Affirmed unanimously on March 12, 2023 at “A Common Cause to All: A Convening of States on the 250th Anniversary of the Call for Committees of Correspondence,” Williamsburg, Virginia. A Common Cause To All Affirmed unanimously on March 12, 2023 at “A Common Cause to All: A Convening of States on the 250th Anniversary of the Call for Committees of Correspondence,” Williamsburg, Virginia. Link: https://va250.org/a-common-cause-to-all/ Photo Credit: Kathy Scott Photography

By Alexander Britell

“Hamilton, you are back!” Under a sunbeam on the water’s edge in Charlestown, Nevis, historian Harvey Hendrickson reads his ode to a still-shrouded sculpture on the lawn. A few minutes later, the bronze is revealed, and Alexander Hamilton is finally back in the place of his birth nearly 257 years after his family moved to St Croix. It was in Nevis that Hamilton, one of the founding fathers of the United States, must have dreamt and aspired and “as a consequence, achieved great things,” Nevis Premier Mark Brantley said. Hamilton, whose towering life returned to the public consciousness with the launch of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Tony-sweeping musical in 2015, was born on the Eastern Caribbean island in 1757, spending his early years in Nevis and then periods of his youth in St Croix and Statia. Hamilton’s extraordinary career included being the first secretary of the treasury, founder of the Federalist Party, founder of the US Coast Guard and arguably the father of the United States’ financial system, among other achievements. Today, Hamilton’s birthplace is a centerpiece of downtown historic Charlestown, Nevis‘ capital, home to a museum and, on the second floor, the site of the Nevis Island Assembly. And Hamilton remains a major draw for the island, which has seen a wave of new tourism interest driven by the reinvigorated public curiosity about Hamilton; the island’s top resort, the Four Seasons Nevis, has an Alexander Suite, for example; there’s even an Alexander Hamilton Rum on sale in the museum shop. Because it all truly did begin in tiny Nevis, and Hamilton’s Caribbean contribution was the subject of a thoughtful ceremony at the Alexander Hamilton Museum in Charlestown this past weekend, one that included a moving appearance by Hamilton re-enactor Scott MacScott. “We, as I like to say, must agree that the United States owes Nevis a debt of gratitude,” Brantley said. In a world where statues and their place are the subject of sometimes tumultuous conversations, the bigger purpose of the Hamilton work is “not to glorify but to recognize the impact that individuals from small island states can have,” said Jahnel Nisbett, director of the Nevis Historical and Conservation Society. The idea is for visitors to come to learn about Hamilton “and leave knowing more about Nevis itself and its rich history,” she said. More broadly, the hope is to inspire young people in Nevis “of the contribution of a Nevisian, that an island this size could have contributed so much to a country the size of the United States,” Brantley said. The life-size bronze statue, donated by Robin Sommers, is part of a series of statues by American sculptor Benjamin Victor, whose first Hamilton statue debuted at the US Coast Guard Academy in 2018. Hamilton, set on the grass in front of his onetime home, is portrayed as a younger man to represent his youth in the Caribbean, carrying a scroll – a symbol of his skills and knowledge, said Nicole Scholet, president of the Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society. The series will also include statues in Statia and St Croix, Hamilton’s other stops in the Caribbean. And now in Nevis, Hamilton is back, peering out at the sea and the streets of Charlestown, the place that by the caprice of history drove him to one day help forge the American Republic. “It’s a welcome addition,” Brantley said. “It reminds us that we are never limited by the station of our birth, only by the extent of our ambition and imagination.” A limited edition Alexander Hamilton rum was created to memorialize the occasion. The Gaspee was a British revenue cutter that was burned by colonists in 1772 in what is now known as the Gaspee Affair. The ship, under the command of Lieutenant William Dudingston, had been enforcing trade regulations in the colony of Rhode Island and had seized several colonial vessels. In June 1772, a group of colonists, led by John Brown, attacked the Gaspee and set it on fire. The incident was one of the early acts of rebellion against British rule in the colonies and was an important event leading up to the American Revolution.

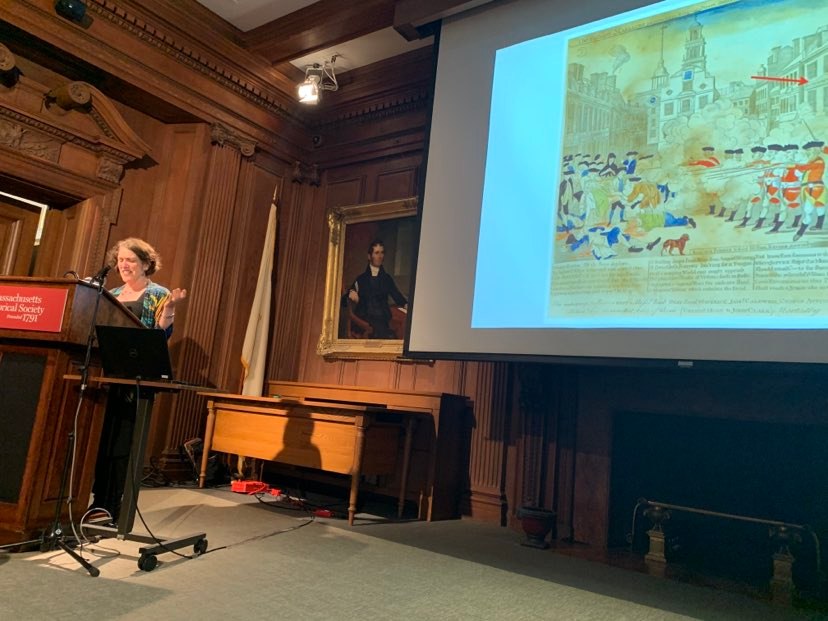

Rhode Islanders commemorated the 250th anniversary of the burning of British customs ship the Gaspee with a recreation of the scene on Sunday, June 12, 2022. The Boston Massacre was commemorated with an evening lecture by historian and author Serena Zabin at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The presentation explored the events leading up to the Boston Massacre of 1770, in which British soldiers killed five colonists during a confrontation in Boston. Zabin provided a detailed account of the social and political context of the time, drawing on primary sources such as court records and newspapers. One of the main focuses of the discussion was about the victims of the massacre and their families, and how they were connected before the outbreak of violence and how they coped with the tragedy. She also explored the role of the press in shaping public opinion and the aftermath of the massacre and its impact on the colonies' relationship with Great Britain.

On the morning of March 5, 2020 the Daughters of the American Revolution hosted a ceremony at the Old Burying Grounds. New York City, the American Revolution, and the Significance of the Number 45

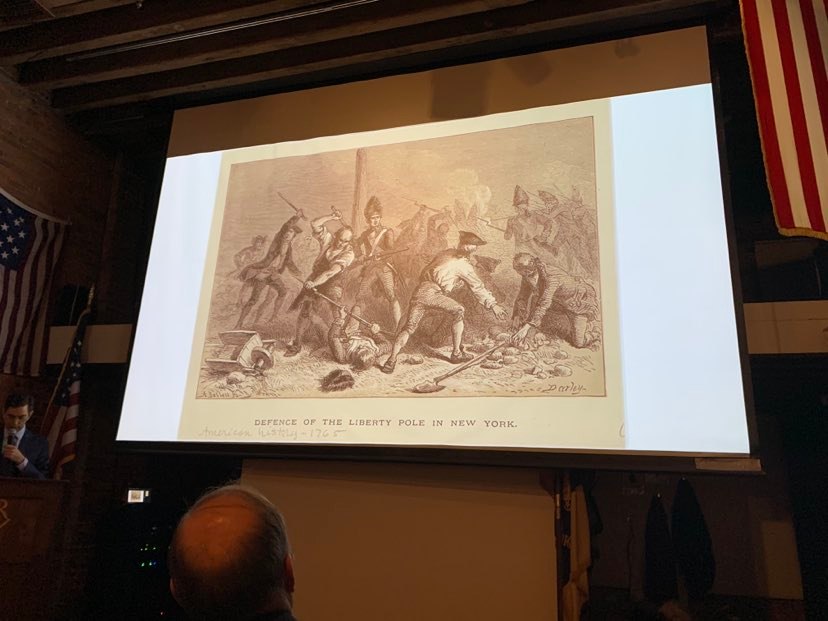

After the end of the French and Indian War, there was tension over King George and Parliament’s plan to tax the Colonies to pay off the war debt. John Wilkes, editor of “The North Briton” newspaper and a member of Parliament, opposed the King in his publications. Wilkes’ most critical editorial was printed in 1763 in Issue # 45, a number highlighted to evoke memories of the Jacobite Uprising of 1745, commonly referred to as “The 45 Rebellion” or simply “45” in political culture. The King was personally offended and issued a warrant for Wilkes’ arrest. As a result, “Wilkes, Liberty, Number 45” lived on as a rallying call against unlawful imprisonment. In New York City, the Sons of Liberty had a tradition of erecting “Liberty Poles” to voice opposition to British oppression. In 1766 they erected a pole in City Hall Park to celebrate the repeal of the Stamp Act. British soldiers chopped it down, the Sons of Liberty put a second one up, and it was chopped down again. The third pole went up and remained unchallenged until a year later in May 1767 when British soldiers noticed the townspeople gathering at the Liberty Pole to celebrate the anniversary of the repeal of the Stamp Act. They destroyed it once again. Undaunted, the Sons of Liberty erected the fourth pole, defiantly larger and wrapped in iron bands. Soon after, the Quartering Act passed, requiring colonists to provide housing to British soldiers. The New York Provincial Assembly refused to support it, so they were prorogued, and the new Assembly approved public funds to be allocated for quartering troops. In response to the Assembly’s reversal, an anonymous broadside began circulating in December of 1769 titled, “To the Betrayed Inhabitants of the City and Colony of New York.” The British soldiers reacted by setting off explosives at the Liberty Pole and leaving the splintered wood on the steps of Abraham Montayne’s Tavern and Coffee House which was located on Broadway, just across from the City Hall Park. On January 19, 1770, the tension erupted into violence when a leader of the Sons of Liberty, Isaac Sears, interfered while British soldiers were posting broadsides of their own at an outdoor market by the East River wharves. Sears captured the offending soldiers and began to march them to City Hall. Other soldiers in a nearby barracks sounded alarm and then pursued the men, but crowds gathered to protect Sears. The crowd overwhelmed the soldiers and the soldiers fired shots into the crowd. Several people were injured. The incident took place in a small patch of grass known as “Golden Hill,” which is today visible only as a slight incline towards the intersection of William and John Street in the Financial district. The Governor of New York offered 100 pounds in cash to anyone willing to reveal the name of the person who wrote the anonymous broadside. After three weeks passed without a response, the Governor ordered all printers in the city to be arrested and jailed. This led to printer James Parker being identified as a person of interest in the case. Parker then revealed that the author of the broadside was a man named Alexander McDougall. A Fifth Liberty Pole was raised on February 6, 1770 on a plot of land owned by Isaac Sears. The next day, McDougall was accused of seditious libel against the Crown and coincidentally, his arrest warrant was number 45. In playing on this numerical association, McDougall became known as “the Wilkes of the Colonies” and demonstrators kept up a constant watch. Every day, supporters appeared at his jail cell to cheer 45 times. Food and drink was shared, including 45 shots of rum, 45 pounds of beef, etc. On the 45th day, the Sons of Liberty brought 45 virgins dressed in white to sing Psalm 45. Newspapers humorously debated if there were really 45 virgins in the whole city to make up such a gathering, and one commenter joked that it was not possible since they were all 45 years old. Because no one wanted the unpopular task of prosecuting McDougall, his confinement and the theatrics of his supporters lasted for three months. McDougall was ultimately released because the sudden death of James Parker, the printer, left the prosecution without any witnesses in the case. The clash between the Sons of Liberty and the British soldiers that led to McDougall’s imprisonment is referred to as The Battle of Golden Hill. It is often considered by scholars to mark the “first bloodshed” of the Revolution. The second violent clash, known as the Boston Massacre, occurred six weeks later March 5, 1770 and resulted in five deaths. For a brief time, during the years leading up to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the number 45 was understood as a symbol the American spirit in favor free speech and in condemnation of unlawful use of arrest to silence an opposing voice. For this and many other contributions that Alexander McDougall made to the Revolutionary War, MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village/Soho was named in his honor. All over the former colonies the symbol of the liberty pole persisted for a generation or more. In Newburgh, the population remained in close association and loyalty to George Washington and John Adams during their Presidential administrations. There was even an strong effort to rename the whole Precinct as the “Village of Washington” but it never fully stuck. The revolutionary spirit lived on in other ways too. In the 1793, editor Lucius Carey took over the old printing press that had been set up at the Fishkill Supply Depot to print General Orders for distribution, he established Newburgh’s earliest newspaper called the Newburgh Packet, then in 1798 a second local publication was introduced. The Mirror was edited by Philip Van Horne. Van Horne, a transplant from New Jersey, wrote avidly against the Federalist party and when the Sedition Act of 1798 was passed by Congress, Van Horne was among those arrested for his politics. In response, recalling the traditions of revolutionaries in the pre-war period, his local supporters erected a liberty pole in Newburgh. Not too much is known about the circumstances, but locals viewed it as a sedition pole and called it such, appearing as a mob to tear it down. |

Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed